The 1958 Belgian Dinner Experiment

The 1958 Belgian Dinner Experiment

-

-

-

-

-

The 1958 Belgian Dinner Experiment

-

Post #1 - January 23rd, 2006, 1:01 pm

Our city has become famous for chefs on the cutting edge of experimental restaurant food. But I have the urge to experiment with their exact opposite, the foods you can find in no restaurant-- but that were once part of everyday life. I love to read about the ways people ate in the past; how they made the best of what they had, in a time before overnight airshipping from Chile and when heirloom varieties were still just tomatoes, three for a dime. How people ate like their people had eaten for centuries... yet in a way that no one anywhere eats, just a few decades later.

This is the story of one such experiment in historical dining.

* * *

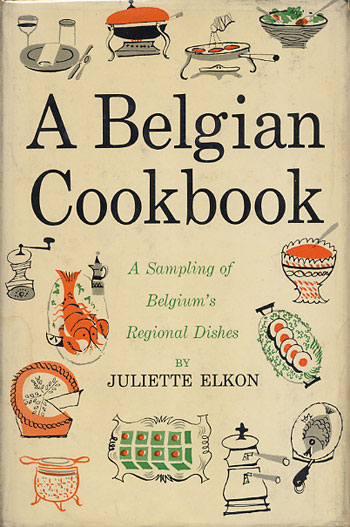

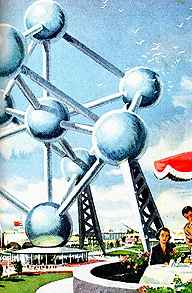

A while back I was in that rare thing today, a used bookstore (The Armadillo's Pillow up in Rogers Park) and I spotted a cookbook on the shelves which sang to me. Partly it was the quaint retro graphics, which could have decorated any cookbook at the time, but partly also it was the fact of its mission-- to educate the housewife of the 1950s on a particular European subspecialty, the cuisine of Belgium. Indeed, the cuisines plural, since tiny Belgium splits, like Atomium--

--into even smaller particles, gastrons and cuisinitrons with names like Flanders, the Kempen, the Ardennes.

An antique Belgian cookbook called out to me more than, say, a Danish or a Swiss one because, even though neither of us traces any ancestry there, Belgium has a sentimental place in the lives of my wife and I. My wife actually spent her first-grade year there while her father did aeronautical research at the Von Karman Institute-- and her mother spent much of her time taking a cooking course, one of the recipes she learned even making its way alongside homey American dishes in the Wichita Junior League cookbook still given to Kansas brides on their wedding days. (In memory of one fixture of that cooking class, a scullery maid who cleaned up silently after every session, my mother-in-law still greets a post-cooking mess with "I need a little Belgian lady.")

Several days of our honeymoon in 1990 were spent in Bruges, an indescribably lovely city of medieval buildings and canals, sipping peach lambic and eating cheese on the lawns of convents and colleges. (My forays into beermaking in the 90s were launched by the desire to recreate the subtle charm of peach lambic, which unlike the more assertive cherry and raspberry lambics, was difficult to find here.) On the same trip, in Brussels, we toured, almost at random out of a guidebook, the dazzling home of the architect Baron Horta (no relation to this) and had a life-changing architectural epiphany, resolving to capture something of his capacity for channeling light through a narrow city house when it came time to renovate our own long, tall, skinny Chicago home.

And last but not least (or then again, maybe it is), the first major scientific dinosaur discoveries were made in Belgium, and it was on another trip in 1988, while lost and searching for the museum where that herd of iguanodons is on display, that I composed my first poem in another language:

Les iguanodons sont perdus

Mes iguanodons, où ête-vous?

Ahem. Anyway, the cookbook was published in 1958, surely not coincidentally the same year Atomium was built, as the 1958 Brussels World's Fair would have been one of the rare times that Belgium did anything to penetrate the American consciousness. Its focus was on home-cooked food more than restaurant cuisine, the author stating that "I have assembled these regional dishes over a period of many years, and in our age of vanishing lore have set them down before they become forgotten. Many have been found in out-of-the-way places where I have watched peasant women at work over their ranges or taken notes from innkeepers in obscure villages." She cites in particular three women to whom she owes both inspiration and experience in the kitchen: her brother's nurse (nanny), Mme. Belleron, "the sister of one of our curés" (ah yes, who has more than one curé these days?), and her grandmother. That the world she describes no longer exists is suggested by the comment of an Amazon reviewer on the best-known contemporary book of Belgian cooking: "Belgian cooking has moved to traiteurs and restaurants, and with all those people working and not cooking, incomes have improved, and they eat out for both the classics and for upscale cuisine."

But of course, for the experimenter in America in 2006, recreating the recipes in this book means entering one lost world through the doorway of another. The recipes are Belgian cuisine of the decades before 1958, but adapted to the shopping and cooking capabilities of the American housewife of 1958, and digging into them one quickly discovers what a different world that is. Many of the recipes seem timid in their seasoning-- saffron (a legacy of Spanish occupation) and mace are about as out there as it gets, even in the few recipes that come from the Congo; and often a dish consists simply of a meat plus egg and perhaps bread crumbs, salted and baked. (Yet at that the recipes are surely lusher than in Mme. Elkon's earlier shot at the topic, The Belgian War Relief Cookbook.) We've become so used to jazzed-up seasonings, food brightened with fluorescent tastes like curry or sun-dried tomatoes or mango salsa, that working with such a restrained palette (and palate) would be an experiment in itself.

On the other hand, the housewife is expected to have easy access to a range of meats virtually unimaginable today-- partridge or game cock for one, eel for many others, skate liver (what is this, Matsumoto?), sheep's tongues and fresh ham from a young boar (no day-old boar for your family, Mom!). And not just rabbit, but a rabbit or hare specifically "past its tender age," liver and giblets included. She is also expected to be comfortable with grisly chores which would drop today's power moms in a dead faint-- "Clean brains by taking out black veins and membranes," reads the quease-inducing, Lecterish opening line of the instructions for one dish, the indelibly named Brain Balls. Only living so close to a rare survivor of the genuine butcher shop era, Paulina Market, would make it even possible for me to pull off many of these dishes-- and even then I would have to compromise on occasion.

So this was my quest, to recreate as best I could the ambitious American housewife's version of the hardworking Belgian peasant woman's daily cuisine in the days of Eisenhower and King Baudouin. (And in doing so I walked in exalted footsteps; it is gratifying to see that the book was not unknown to the most ambitious of American housewife cooks of the era.) My intention was that all the recipes would come from the book-- except dessert; nothing among its simple collection of butter cookies and fruit tarts struck me as being fancy enough to cap the meal (or rescue it if the rest went bad), and so I found another recipe involving both Belgian chocolate and Belgian beer. As it happened, I would bring in another ringer dish along the way, but on the whole I was able to stick to the authentic 1958 Amero-Belgian recipes with satisfaction-- as you will see.

* * *

Mme. Elkon wrote:The pace of life is slow in this benighted province... Supper, except in the more worldly homes, is at 6--simple fare featuring eggs, bread, cheese, patés or pork sausages.

That is how Mme. Elkon describes supper in Flanders, the low countries next to France and facing England, and including Bruges and Ghent. Already being in a charcuterie mood as well as wanting to make as much as possible ahead of time, I looked over Elkon's extensive assortment of pates and settled on an interesting sounding one called Pâté de Lievre, "Hare or Rabbit Pate" (actually a rabbit and pork pate). Here is an example of how different the world of retail meat has become:Mme. Elkon wrote:Have butcher skin, clean and remove bones from a large hare.

Well, there's no large hare for sale, first of all. The only rabbit you'll find, if you find one at all, is the same commercially sold young rabbit, in a sealed plastic bag. And nobody is cleaning it for you, either.

Since I started making this on a Sunday, when Paulina is closed, I decided to try Caputo's instead. They did have fresh rabbit, but turned out not to have some of the other things I needed, such as "fresh ham" and fat back (or as Paulina calls it, "pate fat") for wrapping the pate. I went to Paulina on Monday and then found myself puzzling out with the butcher precisely what "fresh ham" was supposed to mean-- the meat from the hambone, completely fresh, or ham that had been cured but not baked or smoked? We decided fresh hambone meat, but that only rendered the issue that much more academic, since I'd have to buy a whole fresh ham to get my few slices (for the layer you see in the middle). Instead the butcher suggested I buy a rack of ribs; I could slice off the meatiest part in strips, and then still have a nice rack of ribs for later use.

But the rabbit... having handled two rabbits, now, I can honestly say that even more than removing the veins from brains, handling a headless, footless skinned rabbit is the most unnerving bit of butchery I have ever done. As the former owner of both two cats and two babies, the little pink skinless rabbit body is disturbingly close to both as you slice through its leg-flesh to the bone, peel back its torso-flesh from its little ribs. The only thing worse would have been having to remove the Easter bunny's head and skin myself; at least there June Cleaver and I both turned the job over to professionals, even if her mother probably didn't. But all in all, I can't say I'm surprised that rabbit has disappeared from the American housewife's repertoire. You're not going to win the kids over to beheading, skinning and eating Bugs Bunny.

But soon enough, the rabbit, complete with its own liver and giblets, and some chunks of Porky Pig as well, was all being made into an indistinct puree (I've only woken up screaming twice since then), and then marinating in cognac with some salt, pepper and thyme. (The recipe also called for a bay leaf, pretty mysteriously, since there's no liquid for the bay leaf to steep in. I omitted it, frankly.) Simple seasonings; I had to hope that the meats would, with a little accent help from the seasonings, stand on their own. Which is exactly what they did; a reminder (as the entire meal would be) that meats have flavors of their own, and do not always need truffles, garlic, chipotle, or any of the other flavor boosters that have become the mark of sophisticated cuisine today.

* * *

Belgian frites-- which is surely what the world should know them as, rather than French fries-- are one of the simple glories of Belgian cooking, or more to the point, Belgian street life, since they're sold from stands everywhere, served in a bag or cone of paper with mayonnaise on the side (which sounds odd until you've tried hot frites with a really good mayonnaise that tastes like the high quality olive oil it was made with). There's a very good site devoted to Belgian fries here but the instructions in Elkon's book are just as good because they're really quite simple. You have to do the two-step fry to get the proper texture. You have to cut the right size (a little thicker than the McDonald's fry, but not as thick as the Wendy's one).

And you need a good tasty fat. Elkon says "suet, oil or vegetable shortening according to taste," but for me there was only one choice. The experience most people will have had recently with fries done in a bird fat is the duck fat frites offered at Hot Doug's, but I find the duck fat too slippery and light, it doesn't impart much of a flavor of its own. My choice, the most common and to my mind preferred flavor of fried food in Belgium and France, is goose lard. Luckily, this is another standard item at Paulina, where you can buy both the pure white lard and lard with little gribbenes-type crunchies at the bottom. It's not cheap, but I was able to borrow a DeLonghi roto-fryer whose design requires less oil than the traditional fryer, and two tubs proved to be the perfect amount of oil. I experimented with a few different potatoes and cooking temperatures on Friday night-- an activity the kids enjoyed greatly ("We don't need to go to McDonald's, Dad can MAKE French fries!) and quickly found what I considered the optimum combination of temperatures for the two stages, as well as a preferred potato (your basic Idaho russet).

Early in the week I still had the idea of making my own mayonnaise but by the weekend had decided that was one too many new skills to learn. Looking over the rather wan display of Canola mayos and Soyonnaise at Whole Foods, I spotted one jar whose yellowish color suggested that here was real mayo with good flavorful oil and plenty of egg yolks. The label said sunflower oil, not olive, which was bad; but it also said Made in France, which was promising. So I took a chance on a pricey, small jar and was happily rewarded with exactly the rich, old-Europe mayo taste I'd hoped for. So if you make frites, DeLouis Organic Mayonnaise at Whole Foods makes an excellent, flavorful accompaniment. As each batch came out of the fryer, they were pounced upon more readily than any other part of the meal.

* * *

The next dish was the ringer. I wanted to make something for the kids that would keep them fed and happy and out of the way (besides the frites, that is), so I thought I'd make a couple of quick and easy pizzas-- and use the rest of the dough to make something for the grownups which comes from an area not too far from Belgium which my wife had also spent a lot of time in, Alsace. In a word, flammekuchen, or tarte flambee, the highlight of the 2004 Christkindlmarkt (but not the 2005, alas). This time I had an extra treat to put on top-- my homemade bacon.

This is an incredibly easy thing to make, and tasty whether you do it in the oven or on the grill. Make a bread dough (a little whole wheat makes it better, the guys at the Christkindlmarkt added rye which was very good too), shmear on a thick layer of creme fraiche, pepper it generously, dot it with some thin slices of onion and whatever bacony-type pork product you have handy (which you'll probably need to precook somewhat). As with homemade pizza, there's no such thing as a bad one, however you vary the ingredients.

* * *

Along with a host of pates, the book also contains a number of recipes for savory tarts and casseroles, also well suited to being made ahead. Interestingly, several times buttermilk is used as a main ingredient, Mme. Elkin offers both a buttermilk tart and a buttermilk soup, dishes whose peasanty simplicity-- deprivation turned to a virtue-- hardly seems like it could be improved upon. I considered the buttermilk tart before deciding that I wasn't sure if it required old-fashioned real buttermilk, rather than today's cultured kind.

Instead I settled on a leek custard, which is pretty much exactly what it says-- egg and cream baked with leeks, with some salt and pepper thrown in. I overcooked it a little, but again, the simple, clean flavors of a single vegetable and the basic custard around it really came through. It makes you want to go around saying things like "less is more."

* * * Mme. Elkon wrote:The people of the Kempen live on simpler things... I have eaten, on Lenten days, Buttermilk Soup and Knibbekes Torte for supper in my grandmother's kitchen. I have enjoyed Poacher's Stew at many a cottage down in the woods and been regaled with Pears Stewed in Coffee by my brother's old nurse. I have walked to the other end of the village to dip a crusty piece of bread in the sauce of an Estouffade Chevaline at the house of Liske Block, our local midwife... These have been the delights I can never forget--the smells and soft contours of the heath on such a night, the glow of the barbecue pits, the stomping dancers, the beery notes of the local trombone and the warmth and gay truculence of these, my people.

Mme. Elkon wrote:The people of the Kempen live on simpler things... I have eaten, on Lenten days, Buttermilk Soup and Knibbekes Torte for supper in my grandmother's kitchen. I have enjoyed Poacher's Stew at many a cottage down in the woods and been regaled with Pears Stewed in Coffee by my brother's old nurse. I have walked to the other end of the village to dip a crusty piece of bread in the sauce of an Estouffade Chevaline at the house of Liske Block, our local midwife... These have been the delights I can never forget--the smells and soft contours of the heath on such a night, the glow of the barbecue pits, the stomping dancers, the beery notes of the local trombone and the warmth and gay truculence of these, my people.

I read a passage like that and my heart sinks, as no doubt it did for the American housewife cooking from this book 48 years ago; how, in America, land of the rootless and the brand spanking new, can one ever hope to experience life the way these Belgians do, live so deeply and richly, be so in touch with the land and one's neighbors and one's food? And then one remembers what is never mentioned by Mme. Elkon, but hangs over it like a shadow, the reason that her remembrances are so evocative of a lost world, so tinged with melancholy and loss: war. Belgium, a little land run over by army after army throughout the 20th century, its place-names incapable of escaping association with battle-- In Flanders Field the poppies blow/between the crosses row on row. The world she evokes is so evocative because, like the village and the girl found and lost by "le grand Meaulnes," it's always beyond your grasp.

I'll be the first to admit that my main course was not the prettiest plate of food I ever dished up. Since I already had a rabbit theme going, I decided to make Mme. Elkon's poacher's stew, a simple stew of rabbit and partridge with celery root (ultimately pureed as shown above). This is the dish that required an older hare, and here I did run into the limitations of what even Paulina could offer me: not only could I not get an older, more flavorful stew hare, but I had to substitute pheasant for partridge as well. They all went into the stew pot with garlic and thyme, producing a watery mess of clear liquid and softened meat. If the meat was a little on the bland side (as well as surprisingly difficult to tell apart by taste!), the celery root puree was really wonderful, a simple vegetable absorbing all the flavors of the stew and bringing its own peppery, earthy character to it. Again, a very simple dish, austere, the flavors of nature seemingly unmediated by human tinkering; surely better with more flavorful meats, but almost Japanese or Bresson-film-like in its clean, uncluttered flavors.

* * *

As noted, the plan was to go out on a high note of chocolate dessert, and since the book (being rooted in simple home cooking) did not have a host of lush chocolate desserts to whip up, I found a recipe online for a Belgian chocolate cake with a molten center (yes, I know, a concept that did not exist in 1958) and a little beer in its batter. As it happened I'm not sure how many did not in fact bake all the way through, but I think with a little whipped cream on top (which led us, inevitably, to dub it a Belgian Ho-Ho) it hit the spot and capped the evening well.

Interestingly, the one thing that proved problematic about this dish was actually finding Belgian baking chocolate. Piron in Evanston, and also the Leonidas store downtown, both use it, and given more time to drive all over town I might have obtained it from one of them, but none of the places I hit relatively nearby (Whole Foods, Marcey St. Market, Sur La Table, etc.) had an actually Belgian baking chocolate for sale-- French, Spanish, Scottish and lots of upscale American brands, but no Belgian. Of course, since my housewife in 1958 would have been making Elkon's chocolate mousse with Nestle or something, I guess Scharffen Berger wasn't a terrible substitute.

* * *

So ends the experiment in Belgian cooking, and American imitation of Belgian cooking; yet even after a fairly ambitious feast I feel like I have barely begun to explore this old book and the world it conjures up, so many things I dared not even try to make-- the many dishes with buttermilk, with eel as a main meat (eel pie, eels with pot herbs, eel chowder), the names which sound so evocative even before you know what they are-- Coalminer's Omelet, Quail in the Ashes, Lamb Chops Uylenspiegel, Deer Chops With Gin. Will I work my way through this book like Eatchicago plans to work through Bayless' Mexico book? If I do, while he takes a path with a known and much-heralded destination, I will have disappeared down a side road long untraveled in search of a village possibly no longer identifiable. Yet Mme. Elkon, presumably long gone, calls to me all the same. Looking for one of the quotes above I came upon this:Mme. Elkon wrote:In this rich pastureland [Flanders] where fat, placid cows fraze along the canals, where long, low farm buildings stretch along the horizon, veal is milky white and butter has a hazelnut flavor which delicately infuses cream sauces and turns them into a gustatory delight.

Hazelnut butter in a veal sauce... Wait! Wait for me, Mme. Elkon! I can almost see the path... I'm on my way...

* * *

A couple of other quick notes. My guests also got into the theme, bringing Belgian beers (of which this is but a small sample), Belgian chocolates from Piron in Evanston, a Belgian cheese and more. It's surprising how much Belgian deliciousness you can turn up in this city once you start poking around; it really is the overlooked country for significant and top-quality foodstuffs. Special thanks to them for going on this experiment with me (and even playing the part of the little Belgian lady in the home stretch!), and more than special thanks to my wife, King's Thursday, for making it possible to spend the weekend futzing in the kitchen, cleaning up and decorating the house with her own and her parents' collection of vintage 70s Belgian stuff as seen above (including the Atomium pin she wore!), and adding with this dinner to our store of excellent and treasured Belgian memories.Watch Sky Full of Bacon, the Chicago food HD podcast!

New episode: Soil, Corn, Cows and Cheese

Watch the Reader's James Beard Award-winning Key Ingredient here.

-

-

Post #2 - January 24th, 2006, 9:50 amMike G wrote:This is the story of one such experiment in historical dining.

Mike,

Interesting theme enhanced by the amount of thought, and thoughtfulness, you and King's Thursday put into all aspects of the meal. Our knowledge was expanded beyond simply culinary. For example, I now have a burning desire to see the Atomium

Enjoy,

Gary

-

-

Post #3 - January 24th, 2006, 1:31 pmG Wiv wrote:For example, I now have a burning desire to see the Atomium

Admittedly off-topic, but if you're a wine lover, venture to Lussac - just north of St. Emillion - to see the wine lovers' version.

-

-

Post #4 - January 24th, 2006, 11:43 pmnr706 wrote:Admittedly off-topic, but if you're a wine lover, venture to Lussac - just north of St. Emillion - to see the wine lovers' version.

And the beer version is available for sale at Sam's Wine (or at least it was a few months ago when I bought a 4-pack).

http://www.atomiumbeer.com/

-

-

Post #5 - January 24th, 2006, 11:49 pmOh man! I'm pretty sure, having checked that department carefully both for myself and for a friend from out of town, that it's not available at Sam's at the moment, because I sure AS HELL would have bought it.Watch Sky Full of Bacon, the Chicago food HD podcast!

New episode: Soil, Corn, Cows and Cheese

Watch the Reader's James Beard Award-winning Key Ingredient here.

-

-

Post #6 - January 25th, 2006, 8:21 pmMike G wrote:Oh man! I'm pretty sure, having checked that department carefully both for myself and for a friend from out of town, that it's not available at Sam's at the moment, because I sure AS HELL would have bought it.

Actually, it was at the Sam's in Downers Grove. They still had some as of a couple of weeks ago.

Tim

-

-

Post #7 - January 26th, 2006, 7:33 amGreat dinner! The only possible item missing was the famous Cream of Watercress soup learned by my mother in her Belgian cooking class. It is just as well since she always described it as "Cream of Cream" soup.Last edited by King's Thursday on May 20th, 2006, 5:16 pm, edited 1 time in total.We have the very best Embassy stuff.

-

-

Post #8 - January 26th, 2006, 8:29 amMike G wrote:It makes you want to go around saying things like "less is more."

petit pois and I were honored to attend this experimental dinner. I was personally struck by the layers of experimentation that Mike outlines above: Experimenting with a foreign cuisine filtered through time (almost 50 years) and interpretation (recipies designed for the American housewife) which results in an experiment in taste.

This (highly successful) experiment can best be served by a motto of "less is more". The pate, leek custard, and bird/hare w/root puree all drew your palette towards a distinct appreciation of the ingredients (and all went very well with an ale). Completely unclouded by aggressive innovation, these dishes worked because of their elegant and rustic simplicity.

As for the frites, tarte flambe, and chocolate cake: Who has anything bad to say about fries, bacon pizza, and ho-hos?

Thanks again for this meal and also for documenting it here. It has piqued my curiosity in other mid-century cookbooks based on foreign cuisine.

A couple other notes:

--I recently saw an episode of the strangely alluring "Everyday Food". In this episode, one of the hosts visited a butcher who outlined parts of the pig. "Fresh ham" came up and was referred to as ham meat, completely fresh, uncured and unsmoked. I see this regularly at Tony's on Elston.

--Piron does indeed sell large bars of the Belgian baking chocolate that they use.

--My favorite ale of the night was Afflingem. An "abbey ale" with a nice balance of hops and honeyed sweetness.

Best,

Michael

-

-

Post #9 - January 26th, 2006, 1:49 pmLovely post which brought back memories of living with Belgian friends outside of Antwerp for part of the summer of 1970. I quickly fell in love with the frites and mayo-based sauces, chervil soup, endive with cheese sauce, and eel with some kind of creamy green sauce. I was in high school and didn't cook much, so neglected to collect recipes. But for 4th of July I fixed them a midwestern American dinner of spare ribs, corn on the cob (not easy to find) and an approximation of Jello which they stared at in horror before bravely attempting to eat.

-

-

Post #10 - January 30th, 2007, 11:56 am

...Round 2

Almost from the moment I finished clearing the tables from my dinner out of Juliette Elkon's book last year, I thought about having another go at cooking out of her cookbook and trying again the double dislocation of preparing in 2007 a 1958 American version of traditional Belgian food. There were other dishes that had intrigued me, and I also wanted to try to be more rigorous the next time about following her divisions of recipes by regions. Well, a year passed but Sunday night I finally took another shot in a dinner for a small group.

The main conclusion I'd drawn from last year's meal was that meat quality and flavor were paramount; most of the recipes are minimally seasoned, many specified nothing more than a meat and a béchamel sauce or something equally simple. So it was important to pick dishes where a flavorful ingredient would stand out on its own-- and, just as importantly, where it would be possible to get such a flavorful ingredient at retail and not have to compromise (as with last year's stew, which specified an older, gamier hare and a partridge, and wound up being made with a young hare and a pheasant, and turning out a little bland as a result).

Elkon's 1958 housewives had access to a full range of meats, raised more traditionally than we have today, and they had real butchers to select and prepare the cuts for them. That's been the humbling thing in all of this; for all our amusement at the naivete of the TV dinner-push-button 50s, today's supermarkets full of squares of anonymeat in yellow styrofoam (sometimes one hardly knows where the chicken breast ends and the styrofoam begins) are much further from traditional European foodways than June Cleaver was, even if she did crumple potato chips on top of her casseroles and put a can of Campbell's mushroom soup in every dish. In the end, I could only come close to the selection Juliette Elkon's readers took for granted by haunting either throwbacks to that era (Paulina Meat Market, Halsted Packing House) or Asian markets where squeamishness about meat still recognizable as the animal it came from is unknown. Even so, the meal was not without its challenges-- or traumas....

* * *

Starters: Flanders

Juliette Elkon wrote:The pace of life is slow in this benighted province. There is time for a two-course breakfast. A housewife can sit down for a second cup of coffee at 10 with honey cake perhaps, or raisin bread, and the latest gossip. The main meal in Belgium is at noon. Supper, except in the more worldly homes, is at 6—simple fare featuring eggs, bread, cheese, pâtés, or pork sausages.

Pâté de foie à la Flamande (Flemish pork liver pâté)

Ghentsche Peperkoek (Honey Cake)

Homemade bread from French sourdough culture

Belgian cheeses

Soupe au Lait Battu (Buttermilk Soup)

Flanders is the first region covered in the book and the one with the most appetizer-like recipes-- two facts which one assumes are not unrelated. Not that recipes like the infamous Brain Paste mentioned above ("Cool, mash brains with fork") or even Sheep's Tongue With Mushrooms were ever serious candidates for my dinner, or anybody else's these days, but it seemed logical to start with several Flemish recipes demonstrating the determination of poor farming peoples to use every last bit of animal products-- from organ meats in pâté to a soup made from a dairy by-product.

Though Paulina uses, a butcher told me, about 150 lbs. of pork liver at a time for their own liverwurst, they don't keep it for sale. So while I could find the pâté fat as well as a chunk of their bacon for grinding into it, I had to make a special trip to Halsted Packing House to buy the main ingredient. (Of course, the next day I went to HMart and saw it out in the case. Still well worth the trip.) A simple pâté made with only salt, pepper, thyme and cognac, this had a distinctively strong flavor (unsurprisingly) reminiscent for me of braunschweiger; I had to puree it in two batches and made one coarser than the other so that it would have two different textures.

Guests brought a number of interesting Belgian cheeses, most of them from The Cheese Stands Alone, and they were served with (besides lots of Belgian beer) two breads-- the French bread I've been baking for weeks from a French sourdough starter, and what the book called a honey cake, which is only a cake in the sense of a sweet coffee cake-like bread (and not much like what you get when you do a search for "honey cake," which are usually Jewish recipes for a more cake-like dessert). This has 1/2 cup of rye mixed in with 2-1/2 cups of regular wheat flour, 1/1-2 teaspoons of baking powder and 2 teaspoons of soda (no yeast), a quarter cup of water and a truly daunting amount of honey (1-1/2 cups per loaf). Then it bakes at a low 275F for an hour and a half or more, till the center is done.

Of all the things we had last night, I think this is the one I will make again and again. Interestingly, almost everyone had a similar reaction. The first bite strikes you as rather odd-- it's kind of dry (butter helps), spongy, and the honey flavor is almost like apricot bread or something. It takes 3 or 4 bites to adjust to it and by then nearly everyone really liked it. My kids like it too, so good thing I made two.

The last item from Flanders was one of those recipes whose title had intrigued me last year, but I was worried whether it was pushing something too weird on my guests: buttermilk soup. Elkon actually offers no fewer than two nearly identical recipes for buttermilk-based soups; this one from Flanders adds such luxuriant extravagances as apples and prunes, thus demonstrating the truth of the king of France’s sour observation (no doubt thinking of taxes he’d failed to collect) that “here, all the burghers are kings.”

I think most of us concluded that this would be very hard going without the fruit and the sprinkle of brown sugar-- as with an Indian lassi, the salty sourness of hot buttermilk desperately needs the relief of fruit's sweetness and flavor.

* * *

First Course: BrusselsJuliette Elkon wrote:This is the gastronome’s paradise, where he can dine in elegant restaurants in the style of Brillat-Savarin or rest his foie on the simple fare of the provinces or sit in quaint cafes or ale houses... there, with a tall glass of Gueuze or Faro or Kriek Lambic, highly fermented beers which acquire dignity with old age like vintage wine, one can get from the pushcart vendors nearby a main order of tiny crabs, miniature steamed snails called karicollen, French fried potatoes prosaically served in brown paper bags...

Lamb Ragoût Brabançonne

Frites avec mayonnaise

But first, my trauma story. I had decided to make an eel pie, a recipe from the Kempen, which was the region I had planned on for the rest of the meal. Eels are common enough to this day as a food in Europe, enough to figure in popular culture, the mom starts eating them like crazy in The Tin Drum, Pete Townsend named his music publishing company Eel Pie; and evidently Elkon had reason to consider them easy to find in America, as well, since she provides recipes for Eel Chowder, Barbecued Eel, Eels With Pot Herbs.

I figured my only hope of finding fresh eel was in one of the Asian markets. Sure enough, HMart proved to have a tank of them swirling about. The boys were both excited and repulsed by the idea of shopping for live eel; older son said he wanted to watch everything but the killing, younger son (perhaps not realizing what was about to happen to the eel) announced that if he had an eel he would name it Eelie.

I asked for a two-pound eel. A wizened eel wrangler went over, put on arm-length rubber gloves, got out a net, fished out a two-foot long malevolent black creature and flopped it into a plastic bag and set it on the scale. He knew his eels, it weighed right around the correct amount, as it sat there trying to slither its way out of the bag to wreak vengeance upon me with utter hatred in its primordially dark eye.

Great, I want you to do #5, I said (HMart has a number system for whether you want your fish cleaned, cleaned and deboned, cleaned and pressed, etc.) The answer comes back from the guys with the big knives-- we don't clean eel. You don't want to kill. You want to take home fresh. Easy to kill-- just drop in salt water, it die real fast. That best way!

Meanwhile Eelie is wriggling and writhing like a devil full of sin on the scale, his sleek black form rising from the plastic bag like the unholy undead. I'm thinking, this guy had thick rubber gloves to fish this devil-spawn creature out, and I'm supposed to take it home in a thin plastic bag in a car with my kids and keep it alive in my home until I'm ready to cook it tomorrow, at which point I will dump it live into a pot of salt water and hope it dies quickly, so I can then take it out and gut it and skin it in my kitchen?

What do you suppose the odds are that I will dream of eels loose in the house for months afterward?

And so I too ran up against my limits, how far I was willing to emulate Elkon's housewives (admittedly, her recipes imply that someone else has done much of this grisly work for you, too). Book in hand, kids turning vegetarian as we sped away from the scene of our eelish horror, Eelie reprieved and sent back gasping to the tank, I raced back to Paulina, where by now one of the butchers had become my confidant and adviser on this dinner, having referred me to a source for pork liver and walked me through the course to follow.

I showed him a couple of candidates-- I needed something that didn't require a great deal of attention in the middle of my party-- and he steered me toward a lamb stew (named for the Belgian national anthem and a monument in Brussels) using lamb shoulder, a flavorful cut ideal for the Elkonian task of providing full meat flavor with fairly simple seasoning. And so my middle course became a Brussels course, complete with frites with mayonnaise (the only repeat from last year). I browned the meat and set it atop endive with a little onion, parsley, thyme and clove. This was also the only case where I made an alteration to one of Elkon's recipes-- instead of the 50s housewife's trusty can of beef consomme, I used my own, similarly gelatinous, veal stock.

This was a great dish, truly rich with meaty flavor (any worry that the veal stock might stand out over the lamb's strong gaminess was completely misplaced), and very satisfying with hot Belgian frites cooked in goose lard, the true flavor of European frying (another thing, of course, that was only easy for me to find because Paulina is nearby). Truly a course rescued from the Jaws of defeat, thanks to the-- very typical for 1958, almost unknown today-- resource of a good neighborhood butcher to guide me.

* * *

Second Course: Antwerp and the KempenJuliette Elkon wrote:A guest at many Kempen weddings, I have, in Breughelian peasant cottages, feasted on eel pie, eaten great chunks of kid or suckling pig roasted on the most primitive of spits... These have been the delights I can never forget—the smells and soft contours of the heath on such a night, the glow of the barbecue pits, the stomping dancers, the beery notes of the local trombone and the warmth and gay truculence of these, my people...

Cailles Sous le Cendre (Quail in the Ashes)

Chou Rouge (Red Cabbage)

Bergamottes à l’Aigre-Doux (Sweet-Sour Pears)

Though the Kempen grew wealthier with the agricultural revolution (its tallest building was, and maybe still is, a farmer’s association headquarters) and the discovery of coal, its traditional cuisine was that of a farming, hunting—and poaching—people making the most of what they found. The very name "Quail in the ashes" seemed so evocative of of that culture, and quail seemed the ideal bird for making use of the dying hour of a fire, stuffed with mushrooms and quail liver.

Finding quail was no trick-- the freezer case at Paulina had plenty, two to a pack-- though as it turned out they didn't come with their tiny giblets (which hardly seemed enough to do the job anyway) and so the butcher suggested adding some duck liver, which seemed a reasonable substitute (and which they had frozen in back). I bought dried chanterelle and oyster mushrooms at Paulina, stuffed them with a mix of that plus the duck liver (and a healthy, so to speak, mound of butter), then wrapped them in pâté fat and sealed them in foil:

My plan had been to toss them on the grill, slightly above the charcoal, in my Weber kettle, as a way of simulating the dying-fire effect. One of the other butchers at Paulina suggested buying a bag of wood chunks and letting them burn down, as that would be a cooler fire than charcoal. Sounded good, but I started that fire too early and there was little left by the time the quail went on it. They partly cooked out there, but I had to finish them in the oven. My vision was of a delicious smoky roasted bird with little char bits; the reality was certainly well basted by the fat wrapped outside and the butter stuffed inside, but otherwise didn't have much more character than a boiled supermarket chicken, it certainly didn't live up to the picturesque rustic imagery conjured up by the name.

Better were the sides (not strictly from the Kempen, I admit, but both things that seemed pretty universal to northern European cooking): braised red cabbage and some lightly pickled pears, using the one strong spice that tends to turn up in Elkon's recipes, mace. These were pretty as all get out and very tasty, they may get made again too.

* * *

As I noted before, Elkon's desserts are simple almost to the point of being spartan-- a chocolate mousse is as lush as it gets-- and while some of them might have been nice with fruit in season, in January I stuck with a closer I knew would send everyone out happy-- the chocolate pot from the Balthazar cookbook (seen here in a file photo):

And so ends my second experiment in Belgian cooking. I learned something not only about cooking in a simple way with minimal spices, but about how the much-maligned 50s housewife had certain natural advantages in the kitchen-- or rather, the butcher shop-- which today's Viking stove-owning, Food TV-watching, Whole Foods-shopping yuppie gourmands cannot rival. I have more respect for her ambition as well as for what the results must have been. And I leave Elkon with the last word as a description not only of the meals she described then but, in some small way I hope, of the one she inspired 49 years later:Juliette Elkon wrote:It was my grandmother who taught me most of these Belgian specialties... Her greatest achievement I think was that she made her friends, her children and her thirteen grandchildren feel that sitting down at her dinner able was a truly civilized moment. This was a time not only to fill up on the bounty set before us, but a time to feel alive in all five senses. With intelligent talk and elegant but simple settings it was a leisurely ceremony maturing into the deep emotional satisfaction of something shared. This is at it should be.Watch Sky Full of Bacon, the Chicago food HD podcast!

New episode: Soil, Corn, Cows and Cheese

Watch the Reader's James Beard Award-winning Key Ingredient here.

-

-

Post #11 - February 6th, 2007, 5:52 amMike G wrote:Pâté de foie à la Flamande (Flemish pork liver pâté)

Homemade bread from French sourdough culture

Mike,

An amazing meal, and your attention to detail is both commendable and slightly scary.

While the entire meal was wonderful, two weeks later I still find myself thinking of both the pate and bread, quite memorable.

Enjoy,

Gary

-

-

Post #12 - February 6th, 2007, 10:46 amI am now simply dying to search the city for second-hand book shops, and look for antique cookbooks.

I'm also encouraged to go home and get my great-grandmother's 1897 copy of the Boston School of Cooking Cookbook out of it's protective plastic bag and tackle some of the "lost" recipes.

Thanks for an amazing post, Mike.